TNonNullPtr: UE's bouncer for null pointers!

· 7 min read

Introduction #

If you’ve spent any time writing gameplay code in Unreal’s C++, you know the routine. The code we all have to write.

Before you can safely use a pointer, you have to check it. This defensive habit is essential for preventing crashes, but it often leads to code that looks like this:

1void AMyGameMode::StartRound(const AController* PlayerController)

2{

3 if (PlayerController)

4 {

5 if (PlayerController->GetPawn<AMyCharacter>())

6 {

7 if (PlayerController->GetPawn<AMyCharacter>()->GetMyWeaponComponent())

8 {

9 PlayerController->GetPawn<AMyCharacter>()->GetMyWeaponComponent()->EquipWeapon();

10 }

11 }

12 }

13}

This code is safe, perfectly fine. But it’s not clean. The core intent is buried under layers of validation. What if… we could flip this pattern on its head?

Instead of defensively checking for nulls inside our functions, what if we… could enforce a rule that a pointer is never null when it arrives?

Meet the bouncer - TNonNullPtr

#

Think of TNonNullPtr as a bouncer at a club. Its job is simple, but important. Here’s its code of conduct:

- I do not own the people in the club. My job is just to check them (Non-owning)

- I check everyone’s ID at the door (Non-null guarantee)

- If someone shows up with an invalid ID (

nullptr), I don’t let them in. I stop them right there, right now (Asserts on creation)

TNonNullPtr essentially is a lightweight wrapper that makes a powerful promise: this pointer is valid.

Two layers of protection; compile-time and runtime #

TNonNullPtr provides two levels of security by cleverly using C++ features. Let’s look at the engine code to see how.

- The compile-time guard rail

For blatant mistakes,

TNonNullPtrwon’t even let you compile. InNonNullPointer.h, the constructor and assignment operator fornullptrare explicitly forbidden using astatic_asserttrick.

1 /**

2 * nullptr constructor - not allowed.

3 */

4 UE_FORCEINLINE_HINT TNonNullPtr(TYPE_OF_NULLPTR)

5 {

6 // Essentially static_assert(false), but this way prevents GCC/Clang from crying wolf by merely inspecting the function body

7 static_assert(sizeof(ObjectType) == 0, "Tried to initialize TNonNullPtr with a null pointer!");

8 }

9

10 /**

11 * Assignment operator taking a nullptr - not allowed.

12 */

13 inline TNonNullPtr& operator=(TYPE_OF_NULLPTR)

14 {

15 // Essentially static_assert(false), but this way prevents GCC/Clang from crying wolf by merely inspecting the function body

16 static_assert(sizeof(ObjectType) == 0, "Tried to assign a null pointer to a TNonNullPtr!");

17 return *this;

18 }

The static_assert(sizeof(ObjectType) == 0, ...) is a common technique.

Since no complete type can have a size of zero, this assertion is guaranteed to fail if the compiler ever tries to generate code for these functions. It only tries to do that when it sees you directly using nullptr.

This is why this code fails to compile:

1void AMyCharacter::BeginPlay()

2{

3 Super::BeginPlay();

4

5 TNonNullPtr<AActor> SomeActor = nullptr;

6}

0>[1/6] Compile [x64] MyCharacter.cpp

0>NonNullPointer.h(40,36): Error C2338 : static_assert failed: 'Tried to initialize TNonNullPtr with a null pointer!'

0> static_assert(sizeof(ObjectType) == 0, "Tried to initialize TNonNullPtr with a null pointer!");

0> ^

0>NonNullPointer.h(40,36): Reference : the template instantiation context (the oldest one first) is

0>MyCharacter.cpp(23,22): Reference : see reference to class template instantiation 'TNonNullPtr<AActor>' being compiled

0> TNonNullPtr<AActor> SomeActor = nullptr;

0> ^

0>NonNullPointer.h(37,2): Reference : while compiling class template member function 'TNonNullPtr<AActor>::TNonNullPtr(TYPE_OF_NULLPTR)'

0> UE_FORCEINLINE_HINT TNonNullPtr(TYPE_OF_NULLPTR)

0> ^

0>MyCharacter.cpp(23,32): Reference : see the first reference to 'TNonNullPtr<AActor>::TNonNullPtr' in 'AMyCharacter::BeginPlay'

0> TNonNullPtr<AActor> SomeActor = nullptr;

The compiler sees the nullptr and gives you an error, directly telling where the mistake is, acting as a guard rail before your code even run.

- The runtime bouncer

But what about cases the compiler can’t predict? Perhaps a

nullptrPlayer State? Anullptrdue to other function call failing to return a valid pointer?

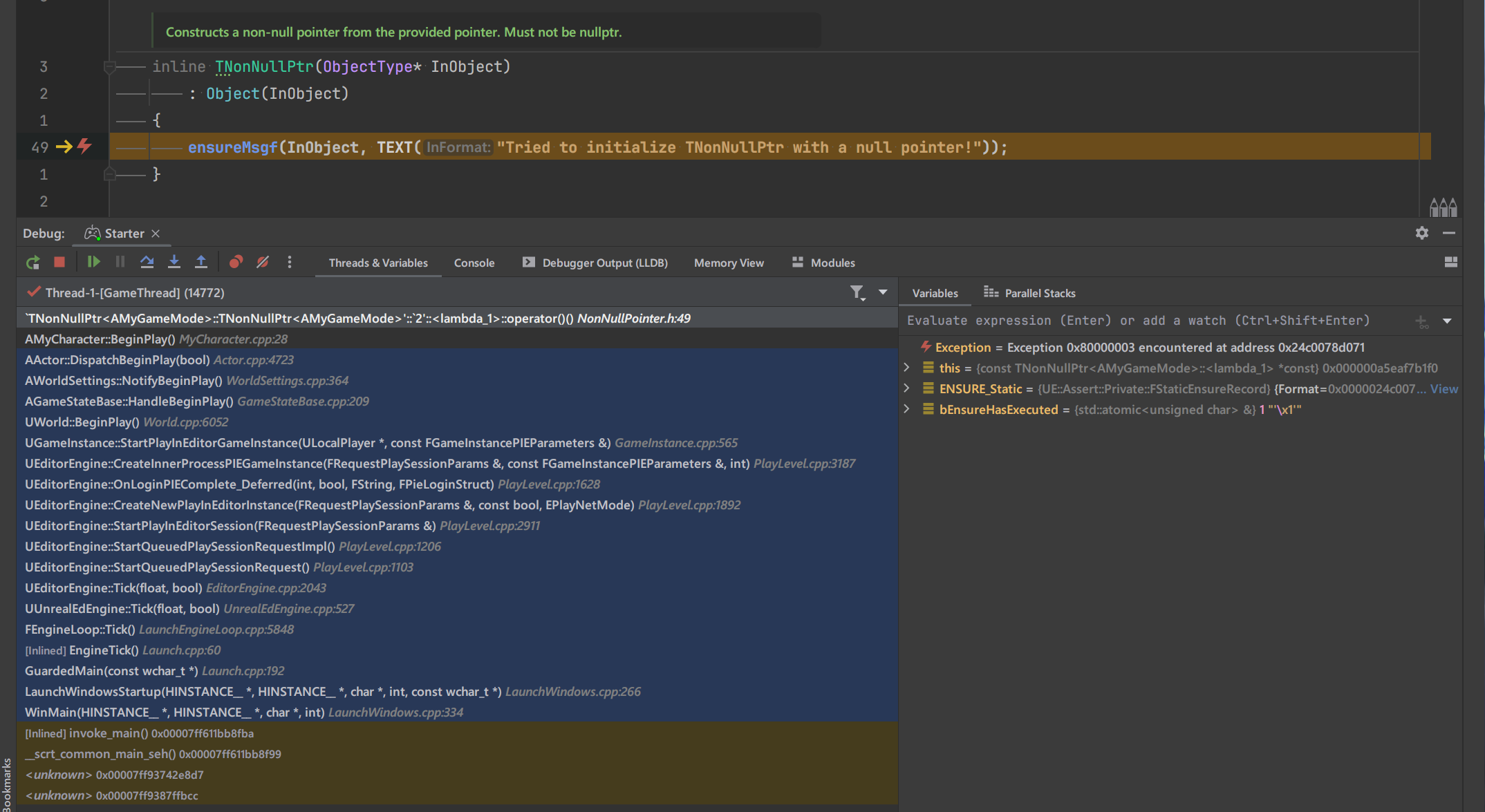

The constructor that takes a regular pointer uses ensureMsgf to validate it.

1 /**

2 * Constructs a non-null pointer from the provided pointer. Must not be nullptr.

3 */

4 inline TNonNullPtr(ObjectType* InObject)

5 : Object(InObject)

6 {

7 ensureMsgf(InObject, TEXT("Tried to initialize TNonNullPtr with a null pointer!"));

8 }

This is the bouncer. When your code runs and a variable that happens to be nullptr gets passed in, the ensureMsgf fires.

1void AMyCharacter::BeginPlay()

2{

3 Super::BeginPlay();

4

5 AMyGameMode* MyFoundActor = Cast<AMyGameMode>(UGameplayStatics::GetActorOfClass(this, AMyGameMode::StaticClass()));

6 TNonNullPtr<AMyGameMode> MyGameMode = MyFoundActor;

7

8 MyGameMode->StartRound(GetController());

9}

This triggers the exception if you’re currently running your project with a debugger attached, where you can inspect the stack trace.

And then inside the output log, you’ll see the following message

LogOutputDevice: Warning: Script Stack (0 frames) :

LogOutputDevice: Error: Ensure condition failed: InObject [File:C:\UE_5.7\Engine\Source\Runtime\Core\Public\Templates\NonNullPointer.h] [Line: 49]

Tried to initialize TNonNullPtr with a null pointer!

LogStats: FDebug::EnsureFailed - 0.000 s

LogOutputDevice: Warning: Script Stack (0 frames) :

LogOutputDevice: Error: Ensure condition failed: Object [File:C:\UE_5.7\Engine\Source\Runtime\Core\Public\Templates\NonNullPointer.h] [Line: 210]

Tried to access null pointer!

Very handy for catching bugs during development!

So, you get the best of both worlds; compile-time errors for obvious bugs and runtime checks for the sneaky ones.

Well then, why isn’t this everywhere? #

You’re probably wondering, if this is so great, why isn’t it the default even for gameplay code?

The reasons are… a mix of game development pragmatism and engine architecture.

- In gameplay,

nullptris often a valid state

In low-level engine code, a null pointer often signifies a critical logic error. But in the fluid world of gameplay, nullptr is a crucial and expected piece of information.

- Optional components, an actor that happens to trigger

OnBeginOverlap()might haveUMyWeaponComponent, but it’s not always guaranteed. - Searching for hit actors, a line trace that hits nothing should return

nullptr - Casting should return

nullptrif the cast fails due to it being a different type or the pointer itself is invalid.

In these cases, nullptr isn’t a bug. Rather, they’re a state that drives a game logic. Using TNonNullPtr here would be incorrect because it would raise an exception on a perfectly valid game state occurances.

check()andensure()are the pragmatic soltion

As established before, the primary benefit of TNonNullPtr is the immediate assert. For gameplay programmers, we already have a way that acheive the same goal with more flexibility.

check(Pointer != nullptr);, functionally the same asTNonNullPtr’s constructor. It crashes with a clear call stack if the pointer is null, enforcing a hard contract.ensure(Pointer != nullptr);often preferred in development builds. It logs an error with a call stack but doesn’t crash it. Perfect for catching “shouldn’t-happen-but-might” bugs without ruining a playtest session.

Adding a single line of check() or ensure() line at the top of a function is far more ergonomic and compatible than changing a type signature.

The mind-shift, with TNonNullPtr ‘spirit’

#

Let’s see how this mindset cleans up a real-world piece of logic

Before: Defensive and paranoid

1// This function must constantly worry about its input.

2void UMyWeaponComponent::ChangeWeapon(UWeapon* NewWeapon)

3{

4 if (!NewWeapon)

5 {

6 UE_LOG(LogTemp, Warning, TEXT("Weapon is null"));

7 return; // Early exit, logic flow is split.

8 }

9

10 // Okay, it's not null, so we can do stuff.

11 NewWeapon->SetAmmo(100);

12}

After: Contractual and confident

1// This function now demands a valid weapon. The _caller_ is responsible for ensuring that the weapon is valid.

2void UMyWeaponComponent::ChangeWeapon(AWeapon* NewWeapon)

3{

4 // The "bouncer" checks the ID at the door.

5 checkf(NewWeapon, TEXT("NewWeapon is null"));

6

7 // No more nested ifs! The code is linear, cleaner and easier to read.

8 NewWeapon->SetAmmo(100);

9}

10

11// The calling code now is forced to be correct.

12void AMyCharacter::NotifyActorBeginOverlap(AActor* OtherActor)

13{

14 Super::NotifyActorBeginOverlap(OtherActor);

15

16 if (AWeapon* Weapon = Cast<AWeapon>(OtherActor))

17 {

18 MyWeaponComponent->ChangeWeapon(Weapon);

19 }

20 else

21 {

22 // We can handle the error here at the source, instead of passing the problem downstream.

23 UE_LOG(LogTemp, Error, TEXT("AMyCharacter::NotifyActorBeginOverlap called with non-weapon actor %s"), *OtherActor->GetName());

24 }

25}

Conclusion #

You will likely never use TNonNullPtr in your gameplay code, and that’s perfectly OK. Its true value lies in the lesson it teaches; make your code’s intentions clear.

- It provides both compile-time guard rails and runtime checks

- It shifts the responsibility for nulls to the caller, where it often belongs

- It turns silent, hard-to-trace crashes into loud, easy-to-fix errors

So next time you write a piece of function, hire a bouncer. Even if it’s just a simple check() at the door. Your future self will thank you.

Acknowledgments #

A special thank you to apokrif6!

I was first inspired to dig into this topic after reading their excellent article, TNonNullPtr — Non-Nullable Raw Pointers in Unreal Engine.

I highly recommend it for a quick, scannable reference guide, especially its fantastic “When to use it?” table.

Thanks for reading, hope it helps and useful for you. See you next time!